HTML First

HTML First Best Practices

These Practices are not Dictatorially Prescriptive. You don't have to strictly follow them all in order to be "Doing HTML First Right".

- Apply The Principle of Least Power

- Prefer Vanilla approaches

- Disfavor Build Steps

- Minimize Client Side State (Use the server)

- Be View-Source Friendly

Apply The Principle of Least Power

When it comes to web languages there's an inverse relationship between the power of the language and how easy it is to learn. Put another way: HTML is the least powerful language but has the lowest learning curve, and javascript is the most powerful but has the highest learning curve. Additionally, the more powerful a language, the easier it is to create footguns and code that is difficult to reason about, debug, and maintain.

The HTML First approach is...

- If you can do it with HTML, use HTML

- If you can't do it with HTML, use CSS

- If you can't do it with HTML or CSS, use Javascript

Related Articles

Prefer "vanilla" approaches over external frameworks

The range of things that browsers support out of the box is large, and growing. Before adding a library or framework to your codebase, check whether you can achieve it using plain old html/css.

An HTML First Approach

<details>

<summary>Click to toggle content</summary>

<p>This is the full content that is revealed when a user clicks on the summary</p>

</details>

A Not Very HTML First Approach

import React, { useState } from 'react';

const DetailsComponent = () => {

const [isContentVisible, setContentVisible] = useState(false);

const toggleContent = () => {

setContentVisible(!isContentVisible);

};

return (

<details>

<summary onClick={toggleContent}>Click to toggle content</summary>

{isContentVisible && <p>This is the full content that is revealed when a user clicks on the summary</p>}

</details>

);

};

export default DetailsComponent;

Avoid Build Steps where possible

Libraries that require transforming your files from one format to another add significant maintenance overhead, remove or heavily impair the ViewSource affordance , and usually dictate that developers learn new tooling in order to use them. Modern browsers don't have the same performance constraints that they did when these practices were introduced, but as an industry we haven't gone back to re-examine whether they're still necessary.

Encouraged

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/styles.css">

Discouraged

<link href="/dist/output.css" rel="stylesheet">

npx css-compile -i ./src/input.css -o ./dist/output.css --watch

The build step practice is so deeply ingrained that even one year ago this opinion was considered extremely fringe. But in the last year has begun to gain significant steam. Some recent examples:

- @dhh - "We've gone #NoBuild on CSS with 37signals"

- Are build tools an anti-pattern by Chris Ferdinandi

- How do build tools break backwards compatibility

- Blake Watson - "There has never been a better time to ditch build steps"

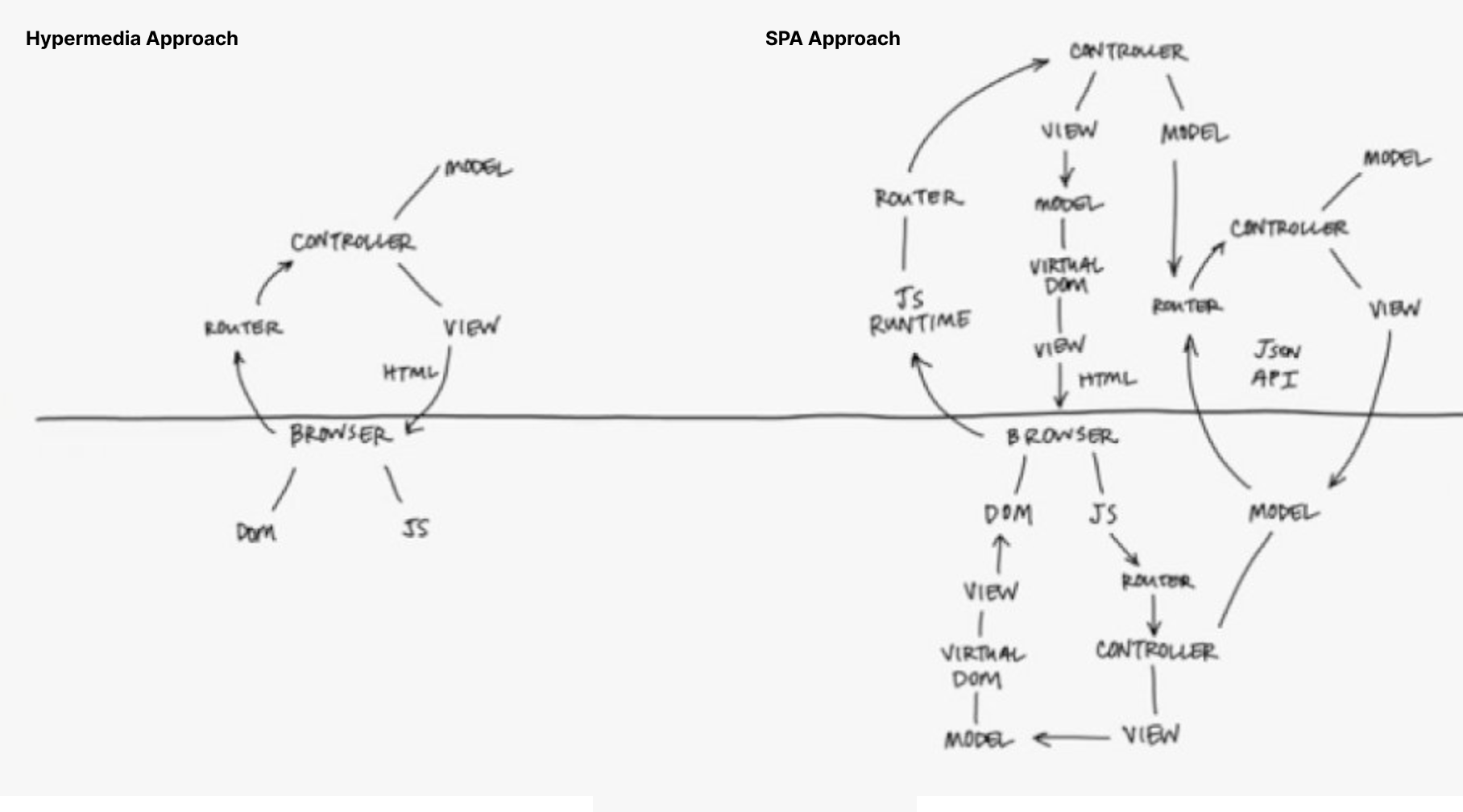

Minimise Unnecessary Client Side State

One of the most common reasons to need heavy build-time preprocessors like react is to handle interactive user input and multi-step forms. In these flows, the information a user enters is validated and collected before it is sent to the server. This invariably leads to needing to recreate many of the concepts that exist on the server, again on the client.

These additional layers of abstraction increase the amount of non-native concepts and substantially increase the complexity of the codebase. One pattern we use often is to create a "draft" record in the database as a user begins a flow, and persist changes and perform validations on the server at each step.

Retain the View-Source Affordance

The beauty of the early web was that it was always possible to "peek behind the curtains" and see the code that was responsible for any part of any web page. This was a gift to aspiring developers, as it allowed us to bridge the gap between the theoretical (reading about how code works) and the practical - seeing both code and interface alongside each other. For many sites, we could copy and paste the html or css and run it ourselves to get a close-to-identical replica. "Remixing" existing snippets was not only a way to learn, but often formed the basis of our new creations.

In the time since, the industry has adopted several practices which have made this practice much rarer. For example, if I write my code with React, the developer who opens Developer Tools on my site doesn't see the original code I wrote, and copy-pasting the code into their codebase won't work.

If you must use libraries, prefer ones that re-purpose existing concepts over those that create their own Lexicon

While we generally recommend avoiding libraries, there are cases where they can be warranted. In such cases, there are libraries that are "HTML First Friendly", and ones that are not. Take this example.

<button hx-post="/results" hx-target="#results">

Fetch Results

</button>

The above is a code snippet that uses HTMX. If I'm already familiar with the web, I'll notice that hx-post="/results is remarkably similar to <form method="post" action="/results">. I'll also notice that the # symbol likely means the code is referring to an element with the id of results, because that's a pattern that's used with CSS selectors.

In fact it's entirely possible that I could read and understand exactly what this code does without ever having heard of HTMX.

Conversely, consider this example

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function App() {

const [results, setResults] = useState(null);

const fetchResults = async () => {

const response = await fetch('/results', { method: 'POST' });

const data = await response.json();

setResults(data);

};

return (

<div>

<button onClick={fetchResults}>Fetch Results</button>

<div id="results">{results && JSON.stringify(results)}</div>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

To understand or change this snippet I'll need to be familiar with several React-specific concepts such as hooks, useState, and the JSX syntax.

A note on Attribute Driven Libraries

A pattern seen often in HTML First Friendly libraries is exposing new html attributes to developers that are not part of native HTML. These libraries are the source of a lot of discussion in the HTML First community.

On the one hand, they violate the "Use Vanilla Approaches" guideline. On the other hand, they elevate the Principle of Least Power (because you can now often write html instead of javascript).

To explore the tradeoffs, lets take an example where we would like to change the background color of an element when a particular button is clicked. With a vanilla approach, we would do something like this:

HTML

<button id="switchButton">Click To Change Status</button>

<div id="status" class="success"></div>

CSS

.success {

background-color: green

}

.failure {

background-color: red

}

Javascript

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', (event) => {

const button = document.getElementById('switchButton');

const div = document.getElementById('status');

let success = false;

button.addEventListener('click', () => {

success = !success;

if (success) {

div.classList.remove('failure');

div.classList.add('success');

button.textContent = 'Set As Failure';

} else {

div.classList.remove('success');

div.classList.add('failure');

button.textContent = 'Set As Success';

}

});

});

This approach works well. It doesn't require the person reading it to have any knowledge of tools or libraries other than the web fundamentals.

At the same time, it does require writing quite a lot of code to do something reasonably straightforward, and because it uses an imperative approach which directly manipulates dom elements, it can be prone to bugs when adding new functionality, unless handled carefully.

Below is an example that does the same thing using an attribute library. This particular example uses Mini, which enables the :click, :class, and :text attributes.

<button

:click="success=!success" // When clicked, toggle the success variable

:text="success ? 'Set As Failure' : 'Set As Success'">

</button>

<div :class="success ? 'bg-green-900' : 'bg-red-900' " ></div>

As you can see, this approach uses less code, but does require contributors to understand new concepts on top of HTML, CSS, and Javascript.

Personally, we consider these types of libraries to still be very much in the spirit of HTML First (our go-to stack is HTMX and Mini.js). But ultimately neither approach is more valid or correct than the other.